Content

[4] Jadunath Sarkar, Mughal Administration, S. C. Sarkar & Sons Ltd., Calcutta, 1935, pp. 3-9.

[5] Savitri Chandra, “Akbar's Concept of Sulh-Kul, Tulsi's Concept of Maryada and Dadu's Concept of Nipakh: A Comparative Study”, Social Scientist, Vol. 20, No. 9-10, 1992, pp. 31-37.

[6] Society, Culture, and the State in Medieval India, in Satish Chandra, Essays on Medieval Indian History, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2010, pp. 51-54.

[7] Setu Madhava Rao Pagadi, The Life and Times of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, in Shiyaji and Swarajya, Indian Institute of Public Administration, Maharashtra Regional Branch, Bombay, 1975, p. 31,

[8] See, M. Athar Ali, The Mughal Nobility Under Aurangzeb, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1997.

[9] Ibn Hasan, The Central Structure of The Mughal Empire, Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi, 1970, pp. 56-63.

[10] The Akbarnama of Abul Fazl translated from Persian by H. Beveridge, Volume II, The Asiatic Society, Calcutta, 1907, p. 421.

[11] Ibn Hasan, The Central Structure of The Mughal Empire, Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi, 1970, p. 62.

[12] H. M. Elliot, Shah Jahan, 1875, pp. 3-5.

[13] Shri Ram Sharma, “Political theory and Administrative Organisation”, R. C. Majumdar (ed.), The History and Culture of The Indian People: The Mughal Empire, Vol. VII, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay, 1974, pp. 522-523.

[14] Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava, The Mughal Empire (1526-1803 A.D), Shiva Lal Agarwal & Company Educational Publishers, Agra, 1986, pp. 177-178.

[15] Shri Ram Sharma, “Political theory and Administrative Organisation”, R. C. Majumdar (ed.), The History and Culture of The Indian People: The Mughal Empire, Vol. VII, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay, 1974, pp. 522-525.

[16] S. R. Sharma, Mughal Empire in India, Lakshmi Narayan Agarwal Educational Publishers, Agra, 1971, pp. 188-180.

[17] Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava, The Mughal Empire (1526-1803 A.D), Shiva Lal Agarwal & Company Educational Publishers, Agra, 1986, pp. 181-182.

[18] Jadunath Sarkar, Mughal Administration, S. C. Sarkar & Sons Ltd., Calcutta, 1935, pp. 22-24.

[19] John F. Richards, The New Cambridge History of India: The Mughal Empire, Part 1, Volume 5, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 63-65.

[20] Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava, The Mughal Empire (1526-1803 A.D), Shiva Lal Agarwal & Company Educational Publishers, Agra, 1986, pp. 184-185.

[21] Ibn Hasan, The Central Structure of The Mughal Empire, Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi, 1970, pp. 234-253.

[22] Jadunath Sarkar, Mughal Administration (Patna University Readership Lectures, 1920), M. C. Sarkar & Sons, Calcutta, 1920, pp. 30-31.

[23] Jadunath Sarkar, Mughal Administration, S. C. Sarkar & Sons Ltd., Calcutta, 1935, pp. 71-75.

[24] M. Jaffar, Mughal Empire from Babar to Aurangzeb, S. Muhammad Sadiq Khan, Peshawar, p. 382.

[25] NCERT Textbook Class XI, 2005, New Delhi, p. 247.

[26] V. D. Mahajan, History of Medieval India, Part II, S. Chand, New Delhi, 2007, p. 236.

[27] Jadunath Sarkar, Mughal Administration (Patna University Readership Lectures, 1920), M. C. Sarkar & Sons, Calcutta, 1920, pp. 62-63.

[28] Stephen P. Blake, “The Patrimonial-Bureaucratic Empire of the Mughals, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 39, No. 1, 1979, pp. pp. 77-94.

[29] Noman Ahmad Siddiqi, “Pulls and Pressures on the Faujdar under The Mughals”,

Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 29, Part I, 1967, pp. 243-255 & Arshia Shafqat and Arshia Shafaqat, The Position and Functions of “Faujdar” in the Administration of Suba Gujrat under The Mughals”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 68, Part I, 2007, pp. 340-350

[30] S. R. Sharma, Mughal Empire in India, Lakshmi Narayan Agarwal Educational Publishers, Agra, 1971, p. 182.

[31] See, Shireen Moosvi, “Mughal administration in rural localities”, Studies in People’s History, Vol. 1, No.2, pp. 231–236.

[32] See, Percival Spear, ”The Mughal ’Mansabdari’ System”, in Edmund Leach and S.N. Mukherjee, Elites in South Asia, Cambridge: University Press, , 1970, pp. 1-15; Fakhar Bilal,

Mansabdari System Under the Mughals (1574-1707), VDM Publishing, 2010 & Abdul Aziz, The Mughul Court and Its Institutions: The Mansabdari system and the Mughul Army ; The Imperial treasury of the Indian Mughuls, Al-Faisal, 2002

[33] Shri Ram Sharma, “Political theory and Administrative Organisation”, R. C. Majumdar (ed.), The History and Culture of The Indian People: The Mughal Empire, Vol. VII, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay, 1974, p. 531.

[34] See, Noman Ahmad Siddiqi, Land Revenue Administration Under The Mughals, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd, 1989 & Lanka Sundaram, Mughal Land Revenue System, The Basheer Muslim Library, England, 1929 & B. R. Grover, Land and Taxation System During the Mughal Age, Originals, 2009.

[35] Meenakshi Jain, Medieval India: A Textbook for Class XI, National Council of Educational Research and Training, New Delhi, 2002, p. 155.

[36] See, Jadunath Sarkar, Mughal Administration, S. C. Sarkar & Sons Ltd., Calcutta, 1935, pp. 106-132 & S. P. Sangar, “Administration of Justice in Mughal India”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 26, PART II, 1964, pp. 41-48 & M. J. Akbar, The Administration of Justice by the Mughals, , Muhammad Ashraf, Lahore, 1948.

[37] See, Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava, The Mughal Empire (1526-1803 A.D), Shiva Lal Agarwal & Company Educational Publishers, Agra, 1986, pp. 492-497 & Muhammad Basheer Ahmad, Judicial System of the Mughal Empire. A Study in Outline of the Administration of Justice Under the Mughal Emperors Based Mainly on Cases Decided by Muslim Courts in India, Pakistan Historical Society, 1978.

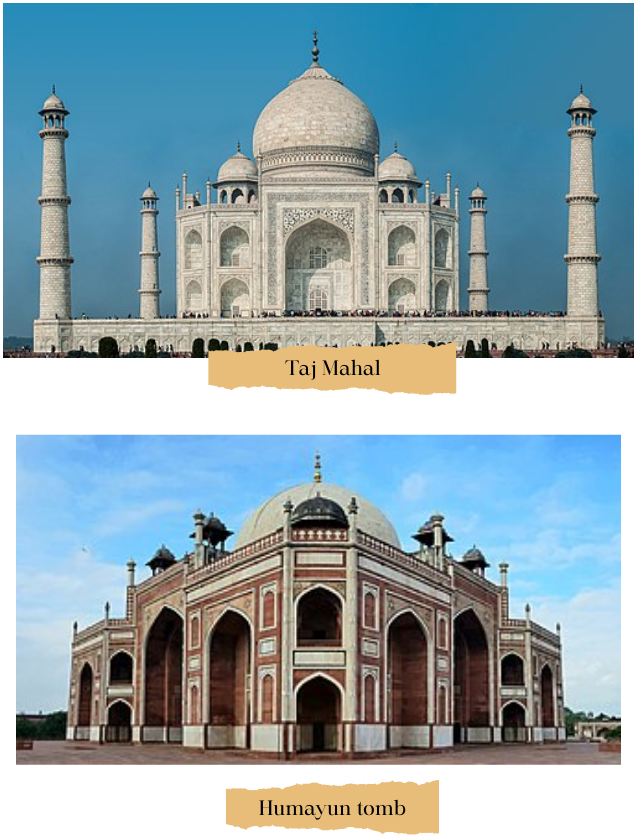

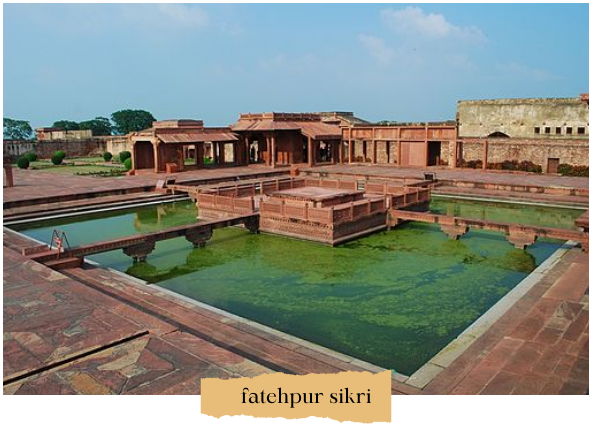

Pictures

Bichitr, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Walters Art Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

© Asitjain/Wikimedia Commons

Rupeshsarkar, CC BY-SA 4.0

Sanyam Bahga, CC BY-SA 3.0

San Diego Museum of Art, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons