Content

[3] Kalikaranjan Qanungo, Sher Shah A Critical Study Based On Original Source, Sri Gouranga Press, Calcutta, 1921, pp. 39-40

[4] Zulfiqar Ali Khan, Sher Shah Suri, Emperor of India, Printed at the Civil and Militray Gazette Press, Lahore, 1925, p. 14

[5] Ibid, pp. 14-15.

[6] J. N. Chaudhuri, “Sher Shah and His Successors”, in R. C. Majumdar (ed.), The History and Culture of the Indian People, The Mughul Empire, Volume 07,Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay, 1974, p. 70.

[7] Ibid

[8] R. P Tripathi, Some aspects of Muslim Administration, The Indian Press Limited, Allahabad, 1936, pp. 352-356.

[9] Satish Chandra, History of Medieval India (800-1700), Orient Blackswan, New Delhi, 2014, p. 222.

[10] J. N. Chaudhuri, “Sher Shah and His Successors”, in R. C. Majumdar (ed.), The History and Culture of the Indian People, The Mughul Empire, Volume 07,Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay, 1974, p. 84

[11] Ibid, pp. 83-84.

[12] Kalikaranjan Qanungo, Sher Shah A Critical Study Based On Original Source, Sri Gouranga Press, Calcutta, 1921, pp. 388-395.

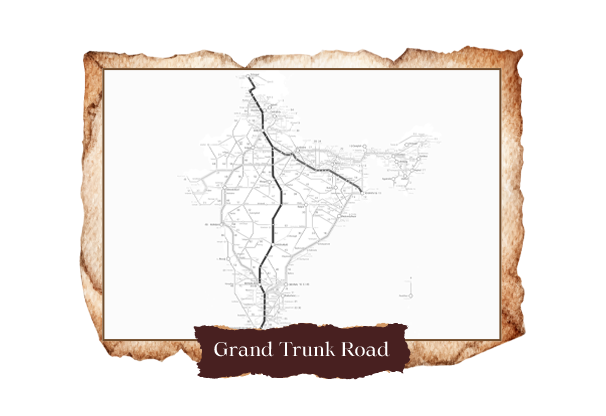

[13] See, K. M. Sarkar, The Grand Trunk Road in the Punjab: 1849-1886, Nirmal Publisher & Distributors, New Delhi, 1998.

[14] Zulfiqar Ali Khan, Sher Shah Suri, Emperor of India, Printed at the Civil and Militray Gazette Press, Lahore, 1925, pp. 92-101.

[15] Ibid, pp. 87-91.

[16] J. N. Chaudhuri, “Sher Shah and His Successors”, in R. C. Majumdar (ed.), The History and Culture of the Indian People, The Mughul Empire, Volume 07,Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay, 1974, p. 85.

[17] Satish Chandra, History of Medieval India (800-1700), Orient Blackswan, New Delhi, 2014, pp. p. 224.

[18] H. M. Elliot and John Dowson, The History of India as told by its own Historians: The Muhammdan Priod, Vol. 4, Trubner and Co., London, 1862, p. 411.

[19] Kalikaranjan Qanungo, Sher Shah A Critical Study Based On Original Source, Sri Gouranga Press, Calcutta, 1921, p. 399.

Pictures

Ustad Abdul Ghafur Breshna, a prominent Afghan artist from Kabul, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

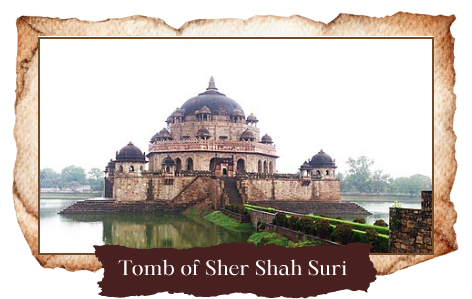

Apleeo, CC BY-SA 4.0

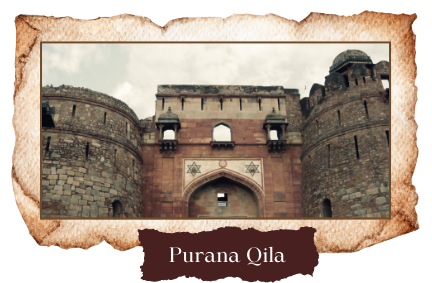

Niteshjha1, CC BY-SA 3.0

Arun Ganesh, CC BY-SA 2.0