Content

[3] C. V. Rangaswami, Government and Administration under the Chalukyas of Badami, PhD Thesis,

Karnataka University, 1969, p. 41.

[4] K. R. Basavaraja, The Administrative System Under The Chalukyas of Kalyana, PhD Thesis,

Karnatak University, 1966, pp. 29-30

[5] Pandurang Vaman Kane, History of Dharmashastra (Ancient and Medieval Religious and Civil

Law) Vol. III, Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Poona, 1946, pp. 17-21.

[6] T. V. Mahalingam, South Indian Polity, University of Madras, 1955, p. 18.

[7] Durga Prasad Dikshit, Political History of the Chalukyas of Badami, Abhinav Publications,

New Delhi, 1958, pp. 197-198

[8] N. Venkataramanayya, The Eastern Calukyas of Vengi, Vedam Venkataraya Sastry & Bros.,

Madras, 1950, p. 279.

[9] C.V. Rangaswami, Administration under the Early Western Chalukyas, Sharda Publishing House,

Delhi, 2015, pp. 31-32.

[10] K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, "The Chaḷukyas of Badami", in Ghulam Yazdani (ed.), The Early

History of the Deccan, Oxford University Press. 1960, p. 209.

[11] Durga Prasad Dikshit, Political History of the Chalukyas of Badami, Abhinav Publications,

New Delhi, 1958, pp. 118-119.

[12] B.R. and M. B. Padma, The Position of Women in Mediaeval Karnataka, University of Mysore,

1993, p. 167.

[13] Durga Prasad Dikshit, Political History of the Chalukyas of Badami, Abhinav Publications,

New Delhi, 1958, p. 199.

[14] G. K. Shrigondekar, Manasollasa of King Somesvara, Vol. II, Oriental Institute, Baroda,

1939, p. 20. & Shiv Shekhar Mishra, Somesvara’s Manasollasa: A Cultural Study, The Chowkhamba

Vidyabhawan, Varanasi, 1966, p. 35-36.

[15] George Buhler, The Vikramankadevacharita. A life of King Vikramaditya Tribhuvanamalla of

Kalyana Composed by his Vidyapati Bilhana, Government Central Book Depot, Bombay, 1875, p.

30.

[16] K. A. Nilkanta Sastri, A History of South India (from Prehistoric Times to the Fall of

Vijayanagar), Oxford University Press, Bombay, 1966, p. 151.

[17] Dhirendra Chandra Ganguly, Eastern Calukyas, Tara Printing Works, Benares, 1937, p.

163.

[18] C. V. Rangaswami, Government and Administration under the Chalukyas of Badami, PhD Thesis,

Karnataka University, 1969, p. 29.

[19] M. N. Joshi, "Social character of Someshvara III", Journal of the Karnataka University:

Humanities, Vol. 29, 1985, pp. 125–126.

[20] P. B. Udgaonkar, Political Institutions & Administration, Motilal Banarsidass, Varanasi,

1986, p. 25.

[21] Ibid, pp. 25-25 & James Campbell, Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, Volume 1, Part 2.

Government Central Press, Bombay Presidency, 1896, p. 221.

[22] T. V. Mahalingam, South Indian Polity, University of Madras, 1955, p. 106.

[23] Kadati Reddera Basavaraja, Administration Under the Chalukyas of Kalyana, New Era,

1983.

[24] See, D. A. Shankar (ed.), Veneration to the Elders: Sivakotyacarya's Vaddaradhane, Manohar

2020 & http://komalesha.blogspot.com/2014/11/the-story-of-sukumaraswami-from.html

[25] C.V. Rangaswami, Administration under the Early Western Chalukyas, Sharda Publishing House,

Delhi, 2015.

[26] Dhirendra Chandra Ganguly, Eastern Calukyas, Tara Printing Works, Benares, 1937, p.

162.

[27] Durga Prasad Dikshit, Political History of the Chalukyas of Badami, Abhinav Publications,

New Delhi, 1958, pp. 214-219.

[28] Indian Antiquity, Vol. XIX, p. 303 & A. M. T. Jackson, “A New Chalukya Copper Plate from

Sanjan”, Journal of Bombay Branch of Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XX, 1902, pp. 40-48.

[29] Dhirendra Chandra Ganguly, Eastern Calukyas, Tara Printing Works, Benares, 1937, p.

163.

[30] C. V. Rangaswami, Government and Administration under the Chalukyas of Badami, PhD Thesis,

Karnataka University, 1969, pp. 115-188.

[31] K. R. Basavaraja, The Administrative System Under The Chalukyas of Kalyana, PhD Thesis,

Karnatak University, 1966, pp. 161-162.

[32] Durga Prasad Dikshit, Political History of the Chalukyas of Badami, Abhinav Publications,

New Delhi, 1958, pp. 221-223.

[33] N. Venkataramanayya, The Eastern Calukyas of Vengi, Vedam Venkataraya Sastry & Bros.,

Madras, 1950, p. 282.

[34] M. Krishna Kumari, Rule of The Chalukya-Cholas in Andhradesa, B.R. Publication Corp., 1985,

p. 134.

[35] C. V. Rangaswami, Government and Administration under the Chalukyas of Badami, PhD Thesis,

Karnataka University, 1969, pp. pp. 267-277.

[36] Krishna Murari, The Caḷukyas of Kalyāṇi, from Circa 973 A.D. to 1200 A.D.: Based Mainly on

Epigraphical Sources, Concept Publishing Company, 1977.

[37] G. K. Shrigondekar, Manasollasa of King Somesvara, Vol. I, Oriental Institute, Baroda,

1925, p. 394.

[38] Durga Prasad Dikshit, Political History of the Chalukyas of Badami, Abhinav Publications,

New Delhi, 1958, pp. 230-232.

[39] Kadati Reddera Basavaraja, Administration Under the Chalukyas of Kalyana, New Era, 1983,

pp. 177-180.

[40] Shiv Shekhar Mishra, Somesvara’s Manasollasa: A Cultural Study, The Chowkhamba Vidyabhawan,

Varanasi, 1966, p.

[41] Durga Prasad Dikshit, Political History of the Chalukyas of Badami, Abhinav Publications,

New Delhi, 1958, pp. 116–118.

[42] M .K. Dhavalikar, “Kailasa — The Stylist Development and Chronology”, Bulletin of the

Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute, Vol. 41, 1981, p. 44.

[43] C. V. Rangaswami, Government and Administration under the Chalukyas of Badami, PhD Thesis,

Karnataka University, 1969, pp. 63-66.

[44] Indumati P. Patil, “The Position of Women during 11th and 12th century (With Special

Reference to Chalukyas of Kalyana)”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 65, 2004,

pp. 126-130.

[45] Krishna Murari, The Caḷukyas of Kalyaṇi, from circa 973 A.D. to 1200 A.D: Based mainly on

Epigraphical Sources, Concept Publication Co., 1977, p. 52.

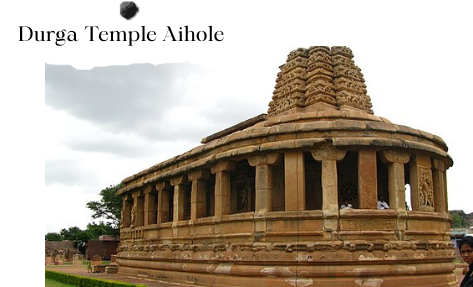

Pictures

P4psk, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Shyamal L., CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Shyamal L., CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia

Commons

Alende devasia, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia

Commons

Shashi.gajare, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia

Commons