Content

[5] Satish Chandra, History of Medieval India, Orient Longman, Delhi, 2007, p. 30.

[6] K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, The Colas, University of Madras, 1955, pp. 460-461.

[7] See, R. Rajalakshmi, Tamil Polity, C. A.D. 600-c. A.D. 1300, Ennes Publications, 1983.

[8] Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, History of India, Routledge, London, 2004, p. 123

[9] R. Sathianathaier, “The Cholas”, in R. C. Majumdar (ed.), History and Culture of the Indian

People, The Struggle For Empire, Volume 05, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Mumbai, 2001, p. 249.

[10] K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, The Colas, University of Madras, 1955, p. 454.

[11] K .A. Nilakanta Sastri, “The Colas”, in R. S. Sharma and K .M. Shrimali (eds.), .A

Comprehensive History Of India Vol. 4 Part I (AD 985-1206),People’s Publishing House, New Delhi,

1987, p. 7.

[12] Ibid, pp. 19-20.

[13] Y. Subbarayalu, “Mandalam as A Politico-Geographical Unit In South India”, Proceedings of

the Indian History Congress Vol. 39, 1978, pp. 84-86

[14] Satish Chandra, History of Medieval India, Orient Longman, Delhi, 2007, p. 31.

[15] Tamil Administration

[16] Burton Stein, Peasant State and Society in Medieval South India, Oxford University Press,

1980, pp. 67-68.

[17] K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, The Colas, University of Madras, 1955, pp. 462-472.

[18] R. Sathianathaier, “The Cholas”, in R. C. Majumdar (ed.), History and Culture of the Indian

People, The Struggle For Empire, Volume 05, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Mumbai, 2001, pp.

252-253.

[19] The Genius of Sanatana Polity and Statecraft: Decolonising Indian Governance by Sandeep

Balakrishna From The Dharma Dispatch, 7 October 2019

https://www.dharmadispatch.in/culture/the-genius-of-sanatana-polity-and-statecraft-decolonising-indian-governance

[20] K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, Studies In Cola History and Administration, University of Madras,

1932, pp. 98-162.

[21] Ibid & K. R. Shankaran, “Tamil Kingship terms in Uttaramerur inscriptions”, in Shrinivas V.

Padigar and V. Shivananda (eds.), Pratnakirti: Recent Studies in Indian Epigraphy, History,

Archaeology and Arts, Vol. I, Agam Kala Prakashan, Delhi, 2012.

[22] Palani Shanmugam, The Revenue System of the Cholas, 850-1279, New Era Publications, 1987,

p. 139.

[23] Ibid, p. 140.

[24] Kesavan Veluthat “Labour Rent and Produce Rent : Reflections on the Revenue System Under

the Cholas (A.D. 850-1279)”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 49, 1988, pp.

138-144.

[25] See, Palani Shanmugam, The Revenue System of the Cholas, 850-1279, New Era Publications,

1987.

[26] K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, The Colas, University of Madras, 1955, pp. 473-480 & S. Tamilponni,

“Judicial Administration of the Imperial Cholas”, Journal of Emerging Technologies and

Innovative Research, Volume 6, Issue 2, 2019, pp. 272-281.

[27] Ibid & Mrs. V. Balambal, “Murder and Punishment under the Cholas”, Proceedings of the

Indian History Congress, Vol. 40, 1979, pp. 83-87.

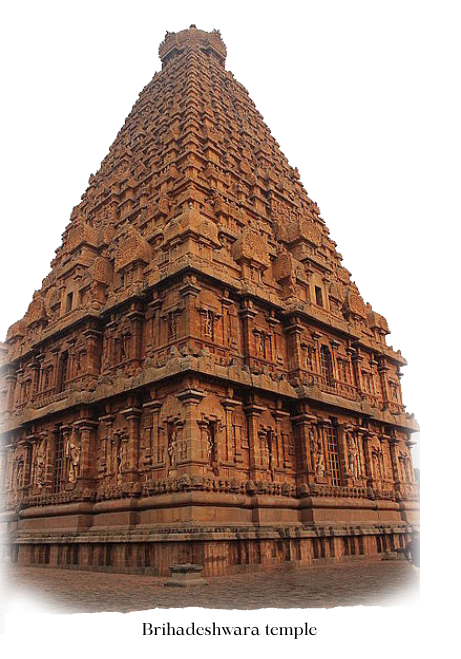

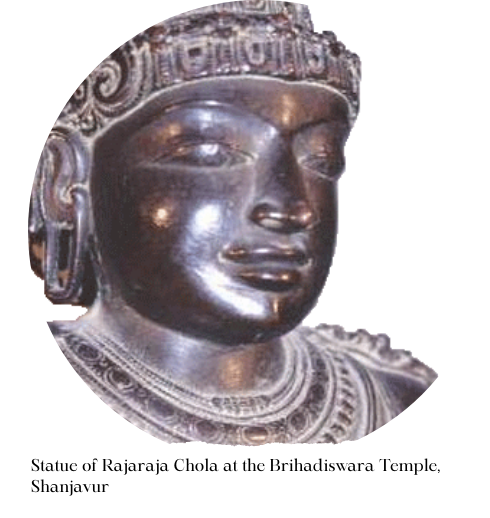

Pictures

KARTY JazZ, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia

Commons

The original uploader was Venu62 at English Wikipedia., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

See page for author, CC BY-SA 2.5 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5>, via Wikimedia

Commons

No machine-readable author provided. Venu62~commonswiki assumed (based on copyright claims).,

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons