Content

[4] Ashirbadi Lal Shrivastav, The Sultanate of Delhi, Shiva Lal Agrawal & Co. (P) Ltd, Agra,

1961, pp. 128-130.

[5] See Shrivastav (1961), ibid. & Kishori Saran Lal, Theory and Practice of Muslim State in

India, Aditya Prakashan, 1999.

[6] Peter Jackson, The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History, Cambridge University

Press, April 1999, pp. 283–287.

[7] John F. Richards, Expanding Frontiers in South Asian and World History, Cambridge University

Press, 2013, p. 55.

[8] Sita Ram Goel, The Story of Islamic Imperialism in India, Voice of India, New Delhi, 1982,

[9] Harsh Narain, Jizyah and The Spread of Islam, Voice of India, New Delhi,

[10] R. C. Majumdar (ed.), History and Culture of the Indian People, The Delhi Sultanate, Volume

06, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, 1967, Bombay, pp. 444-445.

[11] See, Muhamaad Habib and K. A. Nizami, A Comprehensive History of India: Delhi Sultanate

(AD. 1206-1526), Vol. V, Peoples Publishing House, New Delhi, 1970.

[12] See, “Administration in the so-called Slave Kings and Administration of the Sultante”, in

A. L. Shrivastav, The Sultanate of Delhi (711-1526), Shiva Lal Agrawal & Co., Ltd, Agra, pp.

127-139/pp. 282-207.

[13] See, Asif kakar, Role of the Uluma in the Sultanate Era; Sunil Kumar, The Emergence of the

Delhi Sultanate, 1192–1286, Permanent Black, Ranikhet, 2007 & K. A. Nizami, and Ather Farouqui

(ed.), “Delhi under the Sultanate”, in Ather Farouqui (ed.), Delhi in Historical Perspectives,

Oxford University Press, Delhi, 2020.

[14] Wink, Andre, Al-Hind the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: The Slave Kings and the Islamic

Conquest 11th-13th Centuries, Volume 2, Brill Academic, 1991, pp. 124-126.

[15] Iqtidar Alam Khan, “Medieval Indian Notions of Secular Statecraft in Retrospect”, Social

Scientist, Vol. 14, No, 1986, pp. 3-15

[16] Surinder Singh, “Dynamic of Statecraft in the Delhi Sultanate: A Reconstruction from the

letters of Ainul Mulk Mahru”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 61, Part I,

2000-2001, pp. 285-293; N. B. Roy and B. N. Roy, “A Peep into the Delhi Court during the reign

of Sultan Firuz Shah”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 5, 1941,, pp. 313-317 &

S. Jabir Raza, “Epigraphic Evidence for Official and Administrative Offices in the Delhi

Sultanate”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 67, 2006-2007, pp. 312-317.

[17] See, Ishtiaq Husain Qureshi, Administration of The Sultanate of Delhi, Sh. Muhammad

Ashraf, Lahore, 1944.

[18] Hussain Khan, “The Institution of Iqta and Its Impact on Muslim Rule in India”, Islamic

Studies, Vol. 22, No. 1,1983, pp. 1-9

[19] Iqtidar Husain Siddiqui, “Position of Shiqqdar under the Sultans of Delhi”, Proceedings of

the Indian History Congress, Vol. 28, 1966, pp. 202-208.

[20] Krishnaji Nageshrao Chitnis, Medieval Indian History, Atlantic, 2003, p. 163.

[21] Ishtiaq Husain Qureshi, Administration of The Sultanate of Delhi, Sh. Muhammad Ashraf,

Lahore, 1944., pp. 194-216

[22] R. C. Majumdar (ed.), History and Culture of the Indian People, The Delhi Sultanate, Volume

06, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, 1967, Bombay, pp. 453-454.

[23] Fatima Ahmad Imam, “The Administration of the City of Delhi during the Sultanate”,

Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 48, 1987, pp. 179-186.

[24] S. Farrukh A. Jlali. (1976). Administrative Offices in the 13th and 14th century Sultanate

Inscriptions. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress Vol. 37, pp: 532-543

[25] Vijay Lakshmi, Contributions to the economy of early medieval India: Being essays in

interpretations on some obscure economic aspects with special reference to Delhi Sultanate

period, Radha Publications,

New Delhi, 1996

[26] See, Tarikh-i-Firoz Shahi of Ziau-d din, Barni, in H. M. Elliot and John Dowson, The

history of India as told by its own historians. The Muhammadan Period, Vol. III, Turner and Co.,

London, 1871, pp. 93-258.

Pictures

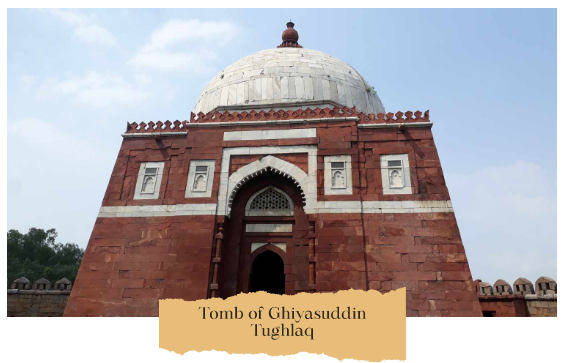

Pinakpani, CC BY-SA 4.0

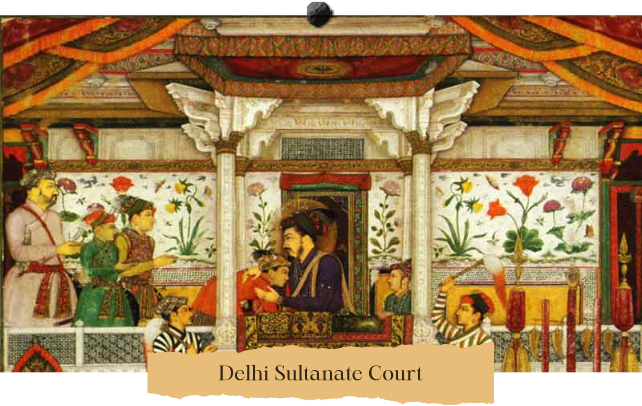

Alimallick, CC BY-SA 3.0

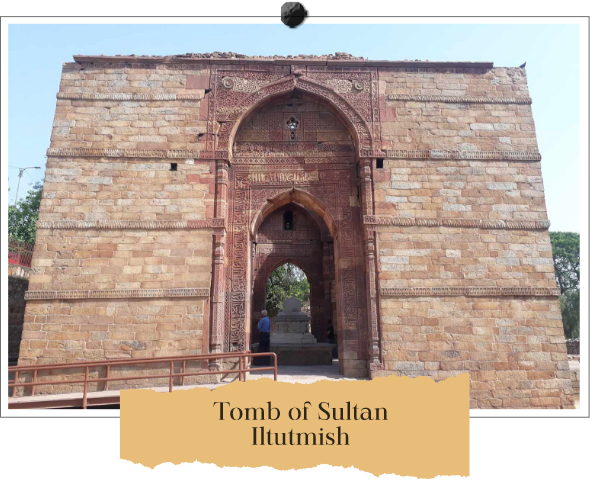

Ankush1830974, CC BY-SA 4.0

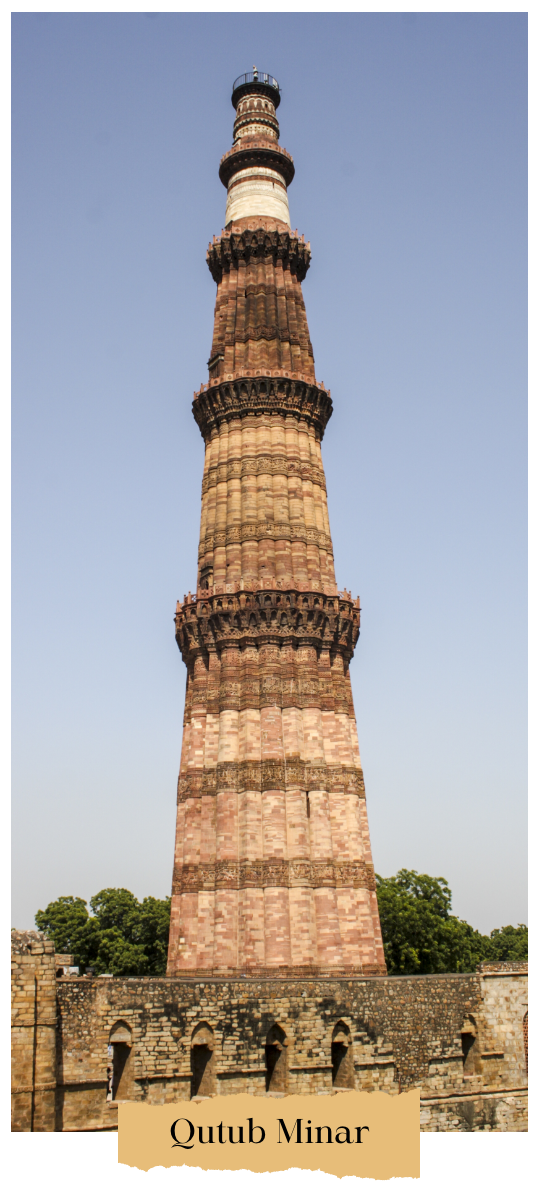

Pinakpani, CC BY-SA 4.0

Indrajit Das, CC BY-SA 4.0