Content

[7] Ashvini Agrawal, Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas, Motilal Banarsidass Publisher Ltd.,

1989, p. 103.

[8] R. C. Majumdar (ed.), A Comprehensive History of India. Vol. 3, Part I: A.D. 300–985,

People’s Publishing House, 1981, pp. 18-20.

[9] V. R. R. Dikshitar, The Gupta Polity, Motilal Banarsidass Publisher Private Ltd., Delhi,

1993, pp. 110-111.

[10] A. K. Warder, Indian Kavya Literature, Motilal Banarsidass, Varanasi, 1989, p. 261.

[11] Dilip Kumar Ganguly, Aspects of Ancient Indian Administration, Abhinav Publication, New

Delhi, 1958, pp. 17-18.

[12] Ramesh Chandra Majumdar and Anant Sadashiv Altekar (eds.), The Vakataka-Gupta Age (Circa

200-550 A.D.), Motilal Banarsi Dass Publisher & Booksellers, Banaras, 1954, pp. 248-251.

[13] Ibid

[14] Dilip Kumar Ganguly, Aspects of Ancient Indian Administration, Abhinav Publication, New

Delhi, 1958, p. 19.

[15] Ramesh Chandra Majumdar and Anant Sadashiv Altekar (eds.), The Vakataka-Gupta Age (Circa

200-550 A.D.), Motilal Banarsi Dass Publisher & Booksellers, Banaras, 1954, pp. 244-255.

[16] Tej Ram Sharma, A Political History of the Imperial Guptas: From Gupta to Skandagupta,

Concept Publishing House, New Delhi, 1989, p. 73.

[17] K. L. Khurana, Ancient India, Lakshmi Narain Agrawal, Agra, 2008, p. 251

[18] K. P. Jayaswal, Hindu Polity: A Constitutional History of India in Hindu Times, Butterworth

and Co., Calcutta, 1924, pp. 163-164.

[19] Hemchanndra Raychaudhuri, Political history of Ancient India from the accession of

Parikshit to the extinction of the Gupta dynasty, University of Calcutta, 1923, p. 279.

[20] The Vakataka-gupta Age Ed. 1st by Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra Edm pp. 247-252.

[21] Dilip Kumar Ganguly, Aspects of Ancient Indian Administration, Abhinav Publication, New

Delhi, 1958, p. 161.

[22] Dilip Kumar Ganguly, Aspects of Ancient Indian Administration, Abhinav Publication, New

Delhi, 1958, pp. 161-162.

[23] Hindu Administrative Institutions by Dikshitar, V.r. Ramachandra, p. 145.

[24] Ramesh Chandra Majumdar and Anant Sadashiv Altekar (eds.), The Vakataka-Gupta Age (Circa

200-550 A.D.), Motilal Banarsi Dass Publisher & Booksellers, Banaras, 1954, pp. 253-254.

[25] A.L. Basham, The Wonder that was India, Picador, 2004, p. 101

[26] Ramesh Chandra Majumdar and Anant Sadashiv Altekar (eds.), The Vakataka-Gupta Age (Circa

200-550 A.D.), Motilal Banarsi Dass Publisher & Booksellers, Banaras, 1954, pp. 254-288.

Raghunath Rai, A History of Gupta Age, Lajpat & Company, Amritsar, 1965, pp. 199-200

[27] Radhakumud Mookerji, The Gupta Empire, Hind Kitabs Ltd., Bombay, p. 154.

[28] Beni Prasad, The State in Ancient India, The Indian Press Ltd., Allahabad, 1928, pp.

298-299.

[29] Radhakumud Mookerji, The Gupta Empire, Hind Kitabs Ltd., Bombay, p. 157.

[30] Makhan Lal, History Textbook for XI, National Council of Educational Research and Training,

2002, pp. 189-190.

[31] Ramesh Chandra Majumdar and Anant Sadashiv Altekar (eds.), The Vakataka-Gupta Age (Circa

200-550 A.D.), Motilal Banarsi Dass Publisher & Booksellers, Banaras, 1954, pp. 262-263.

[32] Radhakumud Mookerji, The Gupta Empire, Hind Kitabs Ltd., Bombay, p. 158.

[33] Ramesh Chandra Majumdar and Anant Sadashiv Altekar (eds.), The Vakataka-Gupta Age (Circa

200-550 A.D.), Motilal Banarsi Dass Publisher & Booksellers, Banaras, 1954, pp. 266-267.

[34] Dilip Kumar Ganguly, Aspects of Ancient Indian Administration, Abhinav Publication, New

Delhi, 1958, pp. 310-311.

[35] Priya Darshani , “Corporate Sustainability During The Gupta Period: A Conceptual Analysis,”

Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 68, 2007, pp. 116-126

[36] Radhakumud Mookerji, The Gupta Empire, Hind Kitabs Ltd., Bombay, pp. 153-154.

[37] Hemchanndra Raychaudhuri, Political history of Ancient India from the accession of

Parikshit to the extinction of the Gupta dynasty, University of Calcutta, 1923, p. 287.

[38] Ramesh Chandra Majumdar and Anant Sadashiv Altekar (eds.), The Vakataka-Gupta Age (Circa

200-550 A.D.), Motilal Banarsi Dass Publisher & Booksellers, Banaras, 1954, pp. 268-269.

[39] Ibid, p. 268.

[40] Radhakumud Mookerji, The Gupta Empire, Hind Kitabs Ltd., Bombay, p. 159.

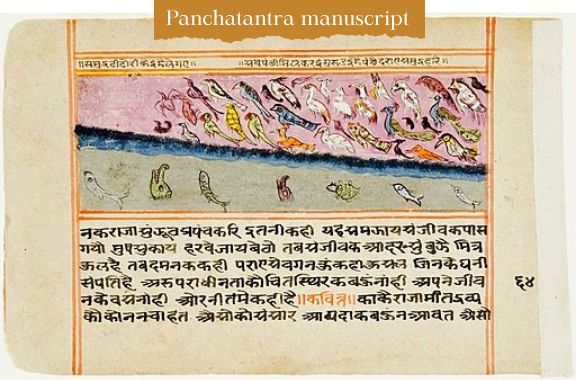

Pictures

CArnoldBetten, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

I, PHGCOM, CC BY-SA 3.0

Artist/maker unknown, India (18th century), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

byron aihara, CC BY-SA 2.0