Content

[5] B. N. Mukherjee, The Rise and Fall of The Kushaṇa Empire, Firma Kala Private Limited, Calcutta, 1988, pp. 324-325.

[6] Ibid, p. 93.

[7] B. N. Puri, India Under the Kushanas, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay, 1965, p. 80.

[8] Ram Sharan Sharma, Aspects of Political Ideas and Institutions in Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, Varanasi, 1968, pp. 217-218.

[9] B. N. Mukherjee, The Rise and Fall of The Kushaṇa Empire, Firma Kala Private Limited, Calcutta, 1988, pp. 313-315.

[10] B. N. Puri, India Under the Kushanas, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay, 1965, p. 80.

[11] B. N. Mukherjee, The Rise and Fall of The Kushaṇa Empire, Firma Kala Private Limited, Calcutta, 1988, p. 329.

[12 Ibid, pp. 326-327.

[13] B. N. Puri, “The Kushans”, in A. H. Dani (eds) History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. II, The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250, UNESCO Publishing, Paris, 1996, p. 262.

[14] A. S. Altekar, State and Government in Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, 1984, p. 210.

[15] B. N. Puri, “Provincial and Local Administration in the Kusana”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 1945, p. 64.

[16] B. N. Mukherjee, The Rise and Fall of The Kushaṇa Empire, Firma Kala Private Limited, Calcutta, 1988, pp. 342-343.

[17] Ram Sharan Sharma, Aspects of Political Ideas and Institutions in Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, Varanasi, 1968, p. 220.

[18] B. N. Mukherjee, The Rise and Fall of The Kushaṇa Empire, Firma Kala Private Limited, Calcutta, 1988, pp. 338-339.

[19] B. N. Puri, “The Kushans”, in A. H. Dani (eds.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. II, The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250, UNESCO Publishing, Paris, 1996, pp. 262-263.

[20] B. N. Puri, India Under the Kushanas, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay, pp. 83-84.

[21] Beni Prasad, “Political Theory and Administrative System,” in R. C. Majumdar (ed.) The History and Culture of the Indian People, Volume II, The Age Of Imperial Unity, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Mumbai, 2001, p. 327.

[22] B. N. Mukherjee, The Rise and Fall of The Kushaṇa Empire, Firma Kala Private Limited, Calcutta, 1988, p. 349.

[23] See, J. W. Mcrindle, Ancient India as Described in Classical Literature. Being a Collection

of Greek and Latin Texts Relating to India, Extracted from Herodotus, Strabo . . . and Other Works., Archibald Constable and Co., Ltd, Westminster,1901.

[24] A. H. Dani and F. Khan, Kushan Civilization in Pakistan, Tsentr. Aziya v kushan.

Cpokhu, Vol. 1, Moscow, 1974. pp. 95-106.

[25] H. A. Litvinsky, Outline History of Buddhism in Central Asia, Moscow, 1968.

[26] Ram Sharan Sharma, Aspects of Political Ideas and Institutions in Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, Varanasi, 1968, p. 223 & Beni Prasad, The State in Ancient India, Stud in the Structure and Practical Working of Political Institutions in North India in Ancient Times, The Indian Press Ltd., Allahabad, 1928, p. 232.

[27] Ibid, p. 224.

[28] B. N. Puri, India Under the Kushanas, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay, p. 84.

[29] Wilfred H. Schoff, “Some Aspects of the Overland Oriental Trade at the Christian Era”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 35, 1915, pp. 31-41 & Sten Konow, “Kalawān Copper-Plate Inscription of the Year 134”, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 4, Oct., 1932, pp. 949-965.

[30] Mortimer Wheeler, Rome Beyond the Imperial Frontiers, G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., 1954, pp. 163- 164.

[31] B. N. Mukherjee, The Rise and Fall of The Kushaṇa Empire, Firma Kala Private Limited, Calcutta, 1988, p. 354.

[32] Ibid, pp. 352-353.

Pictures

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vima_Kadphises#/media/File:Vima_Kadphises_statue_Mathura_Museum.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanishka#/media/File:Kanishka_enhanced.jpg

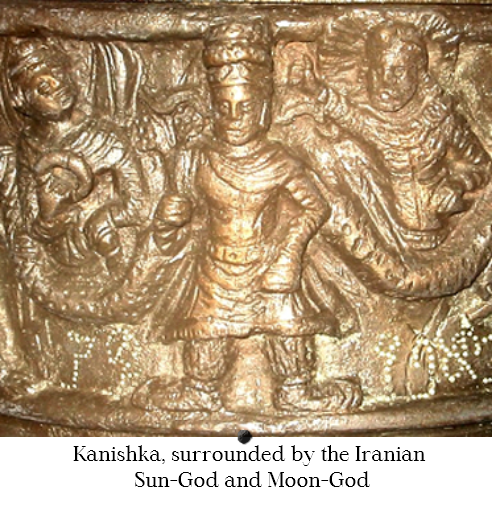

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanishka#/media/File:KanishkaDetail.JPG

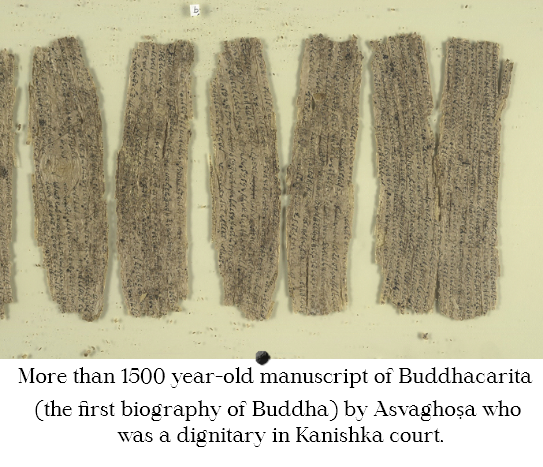

https://dhivanthomasjones.wordpress.com/2022/02/18/re-discovering-treasure-asvagho%E1%B9%A3as-buddhacarita-chapter-15/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanishka#/media/File:KanishkaCoin3.JPG

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vima_Kadphises#/media/File:Vima_Kadphises_with_ithyphallic_Shiva.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanishka#/media/File:Coin_of_Kanishka_I.jpg