Content

[5] Pandit Ramshankar Tripathi, Manishi Chanakya, Pathak and Company, Varanasi, 1964.

[6] Manmath Nath Dutt, Kamandakiya Nitisara or, The Elements of Polity (In English), Printed by

H. C. Dass, Calcutta, 1869, pp. 1-2.

[7] K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, Age of the Nandas and Mauryas, Motilal Banarsidass, New Delhi, 1988.

[8] Narayan Chandra Bandyopadhaya, Development of Hindu Polity and Political Theories, Part 2,

C. O. Book Agency, Calcutta, 1938, pp. 27-28.

[9] For Paura Janpada, see, , K. P. Jayaswal, Hindu Polity (A Constitutional History of India in

Hindu Times) [Part I and II], The Bangalore Printing and Publishing Co., Ltd, Bangalore City, 1,

pp. 255-279.

[10] For Taxation during the Mauryan Empire, see, R. C. Majumdar (ed.), History and Culture of

the Indian People, Volume 02, The Age Of Imperial Unity, Bhartiya Vidya Bhawan, Mumbai, 2001,

pp. 328-330.

[11] For detail information on Administration of Town in Mauryan Empire, see, V. R. Ramachandra

Dikshitar, The Mauryan Polity, University of Madras, 1932, pp. 228-240

[12] V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar, The Mauryan Polity, University of Madras, 1932 p. 172.

[13] V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar, The Mauryan Polity, University of Madras, 1932, pp. 125-135.

[14] See, K. P. Jayaswal, Hindu Polity (A Constitutional History of India in Hindu Times) [Part

I and II], The Bangalore Printing and Publishing Co., Ltd, Bangalore City, 1943, pp. 119-147.

[15] For Police system in Mauryan period, see, Anupam Sharma, “Police in Ancient India,” The

Indian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 65, No. 1 (Jan.-March, 2004), pp. 101-110

[16] Pramathnath Banerjea, Public Administration in Ancient India, Macmillan & Co., Limited,

London, 1916, pp. 290-296.

[17] For more information on Tribal Republics in the North-West India during the time of

Alexander invasion, see, Ramashankar Tripathi, “Alexander’s Invasion in India: A Revised Study,”

Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 3 (1939), pp. 348-370 & A. K. Narain,.

“Alexander and India.” Greece & Rome, Vol. 12, no. 2, 1965, pp. 155–165.

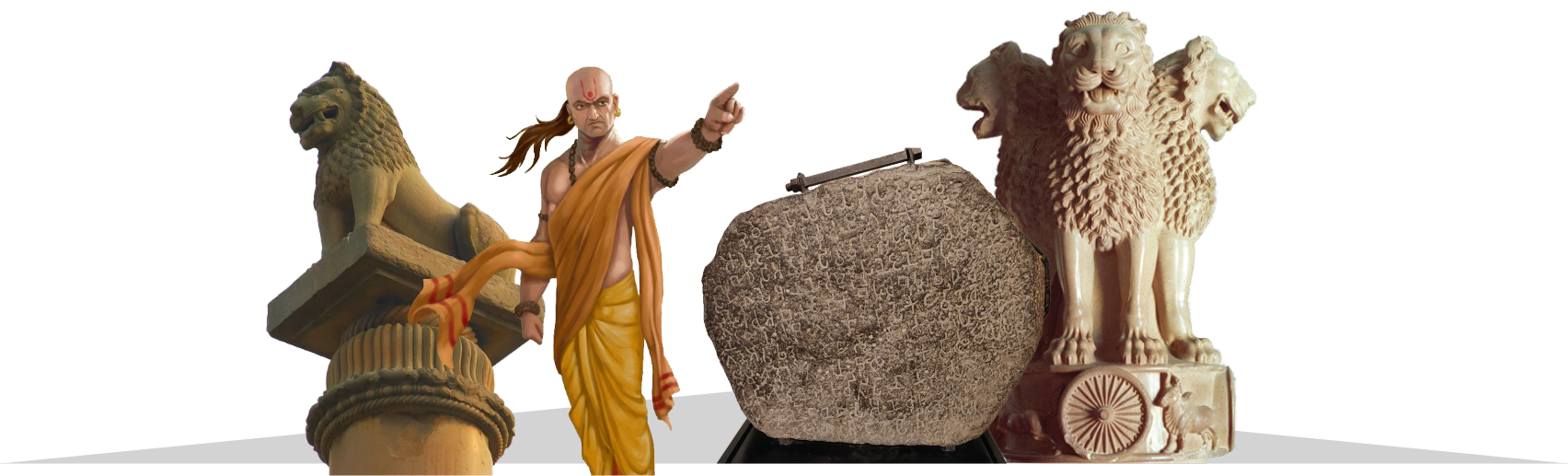

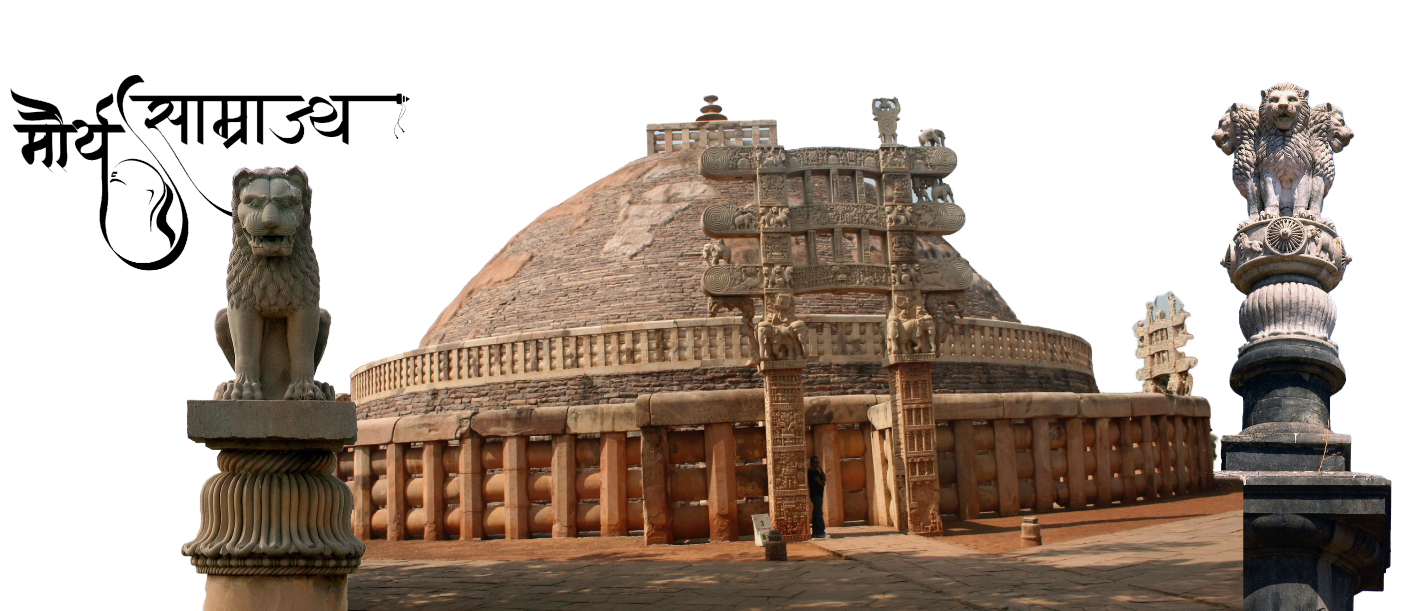

Pictures

Post of India, GODL-India https://data.gov.in/sites/default/files/Gazette_Notification_OGDL.pdf,

via Wikimedia Commons

mself, CC BY-SA 2.5 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

No machine-readable author provided. Vadakkan assumed (based on copyright claims)., CC SA 1.0

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/sa/1.0/, via Wikimedia Commons

Chrisi1964, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia

Commons

Sachin kumar tiwary, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia

Commons

No machine-readable author provided. World Imaging assumed (based on copyright claims)., CC

BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons

No machine-readable author provided. World Imaging assumed (based on copyright claims)., CC

BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons

mself, CC BY-SA 2.5 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Nagarjun, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons A.Savin,

FAL, via Wikimedia Commons