Content

[6] N. Subrahmanian, Sangam Polity: The Administration and Social Life of the Sangam Tamils,

Asia Publishing House, New Delhi, 1966, pp. 35-39.

[7] Ibid, p. 40

[8] N. Subrahmanian, Sangam Polity: The Administration and Social Life of the Sangam Tamils,

Asia Publishing House, New Delhi, 1966, pp. 43-44.

[9] K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, Colas, University of Madras, 1955, pp. 67-68.

[10] K. V. Subrahmanya Aiyer, Historical Sketches Of Ancient Dekhan, The Modern Printing Works,

Madras, 1917, p. 314.

[11] V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar, Studies in Tamil Literature and History, Madras Law Journal

Press, Madras, p. 222.

[12] K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, The Pandyan Kingdom: From the Earliest Times to the Sixteenth

Century, Luzac & Co., London, 1929, p. 87.

[13] N. Subrahmanian, Sangam Polity: The Administration and Social Life of the Sangam Tamils,

Asia Publishing House, New Delhi, 1966, p. 113.

[14] V. Kanakasabhai, The Tamils Eighteen Hundred Years Ago, Higginbotham & Co., Madras and

Bangalore, 1904, pp. 109-110.

[15] V. R. Ramacharan Dikshitar, The Silappadikaram, Oxford University Press, 1939, p. 36.

[16] V. Kanakasabhai, The Tamils Eighteen Hundred Years Ago, Higginbotham & Co., Madras and

Bangalore, 1904, pp. 109-110.

[17] K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, Colas, University of Madras, 1955, p. 69.

[18] N. Subrahmanian, Sangam Polity: The Administration and Social Life of the Sangam Tamils,

Asia Publishing House, New Delhi, 1966, p. 91.

[19] R. C. Majumdar, Corporate Life In Ancient India, Calcutta, 1918, pp. 54-55.

[20] K. B. Rangarajan, “Sangam Age: A Unique Identification of Cultural Heritage of Tamil Nadu”,

IJRAR- International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews, Vol. 5, Issue 3, JULY – SEPT

2018, pp. 737-738.

[21] R. S. Sharma, Ancient India A History Textbook for Class XI, National Council of

Educational Research and Training, New Delhi, p. 167

[22] N. Subrahmanian, Sangam Polity: The Administration and Social Life of the Sangam Tamils,

Asia Publishing House, New Delhi, 1966, p. 110.

[23] K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, Colas, University of Madras, 1955, p. 71.

[24] K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, The Pandyan Kingdom: From the Earliest Times to the Sixteenth

Century, Luzac & Co., London, 1929, p. 90.

[25] T. K. Venkatasubramanian and T. K. Venkatasubramaniam, “Chieftaincies of The Sangam Age A

Developmental Approach”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 42, 1981, pp. 82-94 &

K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, Colas, University of Madras, 1955, p. 71.

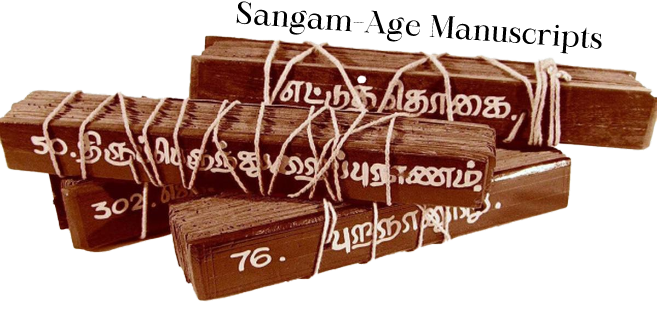

Pictures

Gopikumar.ila, CC BY-SA 3.0

Ms Sarah Welch, CC BY-SA 4.0