Content

[5] K. Gopalachari, Early History of The Andhra Country, University of Madras, 1941, pp. 73-74.

[6] Ibid & K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, A History of South India from Prehistoric Times to the Fall

of Vijayanagar, Oxford University Press, 1958, p. 92.

[7] Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, The History And Inscriptions Of The Sātavāhanas And The Western

Kshatrapas, Maharashtra State Board of Literature and Culture, Bombay, 1981, p. 120.

[8] S. Ramakrishnan (ed.), History and Culture of the Indian People, Volume 02, The Age Of

Imperial Unity, Bhartiya Vidya Bhawan, Mumbai, 2001, pp. 191-206.

[9] G. Yazdani (ed.), The Early History of the Deccan Pat I-VI, Oxford University Press, p. 45.

[10] Sudhakar Chattopadhyay, Some Early Dynasties Of South India, Motilal Banarsidass, Varanasi,

1974, p. 107

[11] R. S. Sharma, Ancient India: A History Textbook for Class XI, NCERT, 2005, p. 158.

[12] R. S. Sharma, “Satavahana Polity”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 28,

1966, p. 82.

[13] Ranjana Mukherjee, The History of Andhra Region c. A.D. 75-350, Thesis Submitted for the

Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, 1965,

pp. 224-225.

[14] Arthashastra, Bk. VI, Ch. 1

[15] Ranjana Mukherjee, The History of Andhra Region c. A.D. 75-350, Thesis Submitted for the

Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, 1965,

pp. 225-226.

[16] M. Monier Williams, A Sanskrit English Dictionary, Oxford, 1899, p. 794.

[17] K. Gopalachari, Early History of The Andhra Country, University of Madras, 1941, p. 148.

[18] A. S. Altekar, “Society in the Deccan from 200 B.C. to 500 A.D”, Journal of Indian History,

Vol. XXX, 1952, pp. 57-69.

[19] Sudhakar Chattopadhyay, “A Note on The Śatavahana”, Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental

Research Institute, Vol. 48/49, Golden Jubilee Volume, 1968, pp. 375-381.

[20] R. G. Basak, The Prakrit Gatha-Saptasati, The Asiatic Society, 1971, p. 61.

[21] Ranjana Mukherjee, The History of Andhra Region c. A.D. 75-350, Thesis Submitted for the

Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, 1965,

pp. 243-244.

[22] R. S. Sharma, “Satavahana Polity”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 28,

1966, p. 85

[23] Beni Prasad, The State in Ancient India, Stud in the Structure and Practical Working of

Political Institutions in North India in Ancient Times, The Indian Press Ltd., Allahabad, 1928,

pp. 222.

[24] Arthasastra, Bk. I, Chapter XX-XXI

[25] Michel Danino, “Woman in Indian history: A few vignettes from epigraphy”, Pragyata,

February 16, 2017

[26] D. C. Sarkar, The Successors of Satavahana in Lower Deccan, University of Calcutta, 1939.

[27] C. Somasundara Rao, “Sectional President's Address: Early History of Andhra Revisited”,

Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 68, 2007, pp. 36-55.

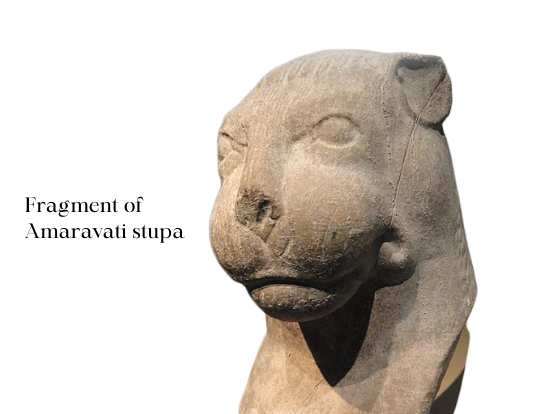

Pictures

Daderot, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

Chetan Karkhanis, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia

Commons