The ideal of the Maratha State (Swarajya) & Kingship

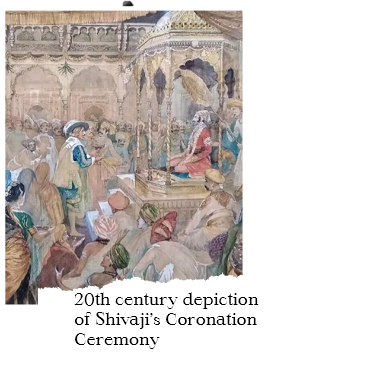

In 1674, Shivaji crowned himself at Raigad and a new era called the ‘Rajyabhisheka

Era’ commenced in the history of India. Shivaji wanted to completely separate from

the Mughal Empire, therefore he commissioned new coinage and regal insignia. Shivaji

took administrative ideas from ancient Indian political writers as he consulted

Mahabharata and Sukraniti and found that government should be vested in the hands of

a council of ministers. The formation of a council of eight ministers popularly

known as Ashtapradhdna by Shivaji and giving them Sanskrit designations, indeed, was

part of his endeavour to revive ancient Hindu political institutions.

[7]

But his real genius of practical statesmanship lay in the manner in which he

successfully blended ancient Indian political institutions with his contemporary

administrative machinery and devised a novel system of administration suited to his

times and his people. Overall, the ancient Indian aphorism that the ruler is the

marker of his age found expression in Shivaji’s idea of kingship.[8]

Contemporary writers considered Shivaji Maharaj an avatar (incarnation) and saw a

divine hand in the foundation of Swarajya.[9] We can well understand

their feelings, considering the almost miraculous achievements of Shivaji. But

curiously enough, even the contemporary foreign accounts lend support to the avatar

theory when they speak of Shivaji in superhuman terms.[10]

The foundation of the Maratha State by Shivaji was a great manifestation of a true

national spirit embodied in the concept of Hindavi Swarajya. Maharashtra during

those times saw many saints from all castes like Shri Chakradhar, Namdeo,

Dnyaneshwar, Eknath, Tukaram, Janabai, and Samarth Ramdas (the guru of Shivaji).

These saints brought great social and spiritual awakenings and produced a new spirit

of democratic equality and homogeneity among the people of Maharashtra. Thus Shivaji

was not only inspired by the teachings of great Maharashtra saints but his quest for

Swarajya was also aided by the widespread spiritual and social enlightenment sparked

by these saints. Shivaji’s teacher, Ramdas gave a religio-political colour to the

Maratha's aspiration of an independent state.[11] Thus, Shivaji came up

as Protector of Dharma (Righteousness) and welded Maratha territory into a single

body politic (Swarajya) on the principal of social harmony and welfare of peasants.

It was Dharma, which formed the root of his Swarajya. It was also his firm belief

that his kingdom was divinely ordained and he used his royal authority for the

well-being of his people.

In an age of bigotry and ruthlessness, he threw careers open to talent and provided

patronage and safety for all of his subjects. In his Swarajya, the welfare of the

peasantry was greatly emphasised. As landlords were often unjust to the cultivators,

he kept them under strict control and he did not create any middlemen between the

government and the tillers of the soil. Shivaji’s letter dated April 1673 addressed

to his administrative and revenue officers speaks volumes about his concern for the

common folk in his country. He writes in this letter:

If you rob the poor cultivators of their grain, bread, grass, fuel or

vegetables, they will find life impossible and run away. Many will die of

starvation. Then they will think that you are worse than the Mughals who overrun

the countryside. Know this well and behave yourself. You have no business to

give the slightest trouble to the ryots. Whatever you want - whether grain,

grass, fuel, vegetables or other provisions — you should purchase it in the

bazaar. There is no need for you to force anybody or to quarrel with

anybody. [12]

His subjects regarded him as their liberator, emancipator, and

protector.[13] The unbounded admiration that the masses had for their

beloved hero constituted Shivaji’s real strength in founding Swarajya.

Ramchandrapant Amatya, who served as the Finance Minister to Shivaji accurately,

reflects the political mind of his Chhatrapati (emperor) in his Adnyapatra (the

formal documentation of Shivaji’s ideals, principles, and policies of state

administration).[14] He provides us with a clear idea of the essential

features of the grand polity of Swarajya. The cardinal principles of Shivaji’s

administration of Swarajya were:

- To promote the well-being of his people and the general welfare of the State.

- To maintain an efficient military force to defend Swarajya.

- To provide adequately for the economic needs of the people by encouraging

agriculture and industry.[15]

Administrative Divisions

The kingdom was divided into Subhas, Sarkars, Parganas, and Maujas both in the Mughal

Empire and the Deccan states. Shivaji replaced this division with Prants, Tarafs,

and Maujas. But the old nomenclature continued to be used for a long time, hence

there is much confusion in identifying territories. There were twelve Prants under

Shivaji. Whereas, civil territory held under the direct sway of Shivaji, was divided

into seventeen districts. Each Prant was put under a Subedar and a Karkun, while the

Taraf was governed by a Havaldar. Shivaji gave Sanskrit names to Subedar and

Sarsubedar who were called Deshadhikari and a Mukhya-Deshadhikari, while the Karkun

and Sarkarkun were named Lekhak and Mukhya-Lekhak (however, the official letters

also carry the old Persian names probably because Sanskrit names did not become

popular.). A few villages were put under the charge of a Kamavisdar. Each Subedar

had generally eight assistants in charge of various duties. They were Dewan,

Muzumdar, Fadnis, Sabnis, Karkhanis, Chitnis, Jamadar and Potnis.[16] The

administrative division can thus be represented as:

Council of Eight Ministers: Ashtapradhdna

Shivaji threw careers open to talent and built up small men to achieve great deeds.

Therein lay his genius as an administrator. Moro Pant Pingle, a family priest

becomes his Prime Minister; Annaji Datto, a village accountant rise to be his

Finance Minister. The men trained by Shivaji faced the greatest generals in battle

and the greatest statesmen in diplomacy. Sonaji Pant Dabir negotiated with Aurangzeb

and Sundarji Prabhu with the English. Prahlad Niraji was the Maratha envoy at the

court of the Qutb Shah. Shivaji aimed at giving equal opportunities for all castes

and creeds in his system of administration. Thus, fully acknowledging the importance

of ministers (Pradhans) in conducting the affairs of the kingdom as recommended in

the ancient Sastras, Shivaji and his mother Jija Bai as early as 1642 appointed

Shamraj Nilkanth Ranzekar as Peshwa, Balkrishna Pant Hanumante as Mujumdar, Sono

Pant as Dahir and Raghunath Ballal as Sabnis. This was the nucleus of what later

developed into the famous Council of Eight Ministers called Ashtapradhdna.

[17]

This Council of eight ministers, Ashtapradhdna acted as Shivaji’s secretaries and

their function was purely advisory. These ministers mainly supervised the details in

their respective departments. It is to be noted that Shivaji never interfered with

the ecclesiastical and accounts departments. Shivaji also specified the duties of

his eight ministers and other departmental heads. It is worth mentioning here that

his Ashtapradhdna was basically a portfolio system based on Sukraniti (ancient

treatise on the science of governance). The names and duties of ministers were

largely adopted from Sukra’s Polity only.[18] The eight ministers and

their duties were the following: [19]

-

Peshwa or Mukhya Pradhan (Prime Minister): He was in charge of the whole

administration of the kingdom. He was to work with the counsel and

cooperation of his colleagues. In times of war, he was to bravely lead the

army, subjugate new kingdoms and make necessary arrangements for the

administration of the newly-acquired territories. All state papers and

charters had to bear his seal below that of the king.

-

Amatya or Majumdar (Finance Minister): He had to check all the accounts of

public income and expenditure and report them to the king, and countersign

all statements of accounts both of the kingdoms in general and of the

particular districts.

-

Mantri or Waqianavis (Political secretary): His duties were to compile a

daily record of the king's doings and court incidents, and to watch over the

king’s invitation lists, meals, and companions, , to guard against murderous

plots. The invitation and intelligence departments were under him. He was

also to serve in the war. His seal was to be put on official documents.

-

Sachiv or Shurunavis (Superintendent): He had to see that all royal letters

were drafted in the proper drafted. He had also to check the accounts of the

mahals and parganas.

-

Sumant or Dabir (Foreign Secretary): He was the king's adviser on relations

with foreign States, war, and peace. It was also his duty to keep

intelligence about other countries, to receive and dismiss foreign envoys,

and maintain the dignity of the State abroad. He was to receive and

entertain foreign envoys and maintain the dignity of the state abroad.

-

Senapati or Sar-i-Naubat (Commander-in-chief): He maintains the army, makes

war, and leads expeditions. He should preserve the newly-acquired

territories, render an account, report to the king the requirements and

grievances of the army, and obtain lands and rewards for the meritorious.

-

Pandit Rao and Danadhyakska (The ecclesiastical head): It was his function to

honour and reward learned Brahmans on behalf of the king, to decide

theological questions, to fix dates for religious ceremonies, to punish

impiety and heresy, and order penances. He was a Judge of Canon Law, Royal

Almoner, and Censor of Public Morals combined.

-

Nyayadhish (The chief justice): He tried civil and criminal cases according

to Hindu law and endorsed all judicial decisions, especially about rights to

land, village headman ship, etc.

Revenue System

The concept of an economically prosperous and flourishing people was intrinsic to

Shivaji’s ideal of Swarajya. He knew that the first duty of a ruler is to make his

people prosper. He strove throughout his life to make his State economically a

viable unit. The way Shivaji protected the tillers of the soil and encouraged

agriculture which formed the backbone of Maratha’s economy, the keen interest that

he showed in developing trade, commerce, and industry in his dominions, and the

various judicious measures that he took to augment the state finances, clearly prove

that Shivaji had a good sense of national economy. Thus, not only did Shivaji

establish Swarajya, but he placed it on a stable and solid

foundation.[20] The splendid achievement of Shivaji is brilliantly summed

up by one of his Astapradhan named Ramchandrapant Amatya in a single sentence, “केवळ

नूतन सृष्टिटीच निर्माण केली” (He created an altogether new order of

things).[21]

Shivaji’s kingdom consisted of territories he wrested from the Sultans of Ahmadnagar

and Bijapur and Mughal emperor. Thus different revenue systems were prevalent in the

Maratha kingdom. In the newly acquired territories, the ryots were formerly been

subject to hereditary landlords collectively called mirasdars who had grown powerful

and cruel in collecting taxes. Shivaji dismantled their castles, garrisoned the

strong places with his troops, and took away all power from the mirasdars. They were

brought under control and their dues were fixed after calculating the exact revenue

of the village.[22] Moreover, the ryots were not subject to the authority

of the feudal lords, who were neither given the right to interfere in the revenue

management of the country nor had the right to exercise the powers of a political

superior (overlord) over ryots or harassing them. [23]

Most importantly, Shivaji tried to bring financial unity by establishing one common

method for the collection of revenue. For this, he revived Malik Ambar’s (He was

Peshwa (Prime Minister) of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate in the Deccan region credited

with carrying out a revenue settlement of much of the Deccan) revenue system and

land in every province was surveyed for assessing the rent and other dues payable by

the cultivators. The main features of Ambar’s system accepted by Shivaji were (i)

the classification of lands according to fertility; (ii) ascertainment of their

produce; (iii) fixing the government share; (iv) collection of rents either in kind

or money and (v) abolition of the intermediate collecting agents as farmers of the

revenue. Using the Tagai and Istawa principles new lands were brought under the

plough and the farmer was subsidized with seeds and cattle. New cultivators were

given seeds and cattle, and loans advanced to them were recovered over years. The

cultivable wastelands were excluded when a village was assessed. When later, some of

the wastelands were brought under cultivation; they were taxed moderately to begin

with. [24]

Besides land revenue, many other sources contribute to the state treasury such as

customs, transit duties, judicial fees, and fines, forest revenue, profits of

mintage, presents by subjects and officers, escheat and forfeitures, plunder of

hostile territory, war booty, capture of ships, various kinds of cesses and last but

not the least Chauth and Sardeshmukhi. Chauth was essentially a tax paid by those

kingdoms that did not want the Marathas to enter their realm. The Chauth thus served

as protection money against Maratha invasions of the chauth paying state. It was an

annual tax levied at 25% on revenue or produce. Sardeshmukhi, on the other hand, was

an additional tax of 10% which Shivaji claimed from the hereditary overlord of

Maratha territory.[25]

The Judicial System

Under Maratha State, Manusmriti, Sukraniti, Yajnavalkya Smriti, Vyavahara Mayukha,

and Kamalakara were referred to as authorities in legal disputes. In civil suits,

the decision was given after consulting the Mitakshara. To settle cases of varying

nature, many sabhas were established as judicial bodies. The most important judicial

body was Raj Sabha constituted of the king, his ministers, important officers of the

kingdom, and persons of the place in which the dispute had arisen. The case of the

Kharade brothers versus Kalbhar brothers about the Patilship of village Pali is

worthy of mentioning here as it was heard by the council consisting of Shivaji,

Peshwa, Nyayadhish, Panditrao, Mujumdar, Senapati, other important officers,

Desbmukhs, Deshpandes, and Patils of the village Pali. Here we find the procedure

adopted in hearing and deciding suits. It was found that the case could not be

decided on the available evidence. Therefore the complainant had to undergo an

ordeal. Therein he failed and hence he lost his case. [26]

Among other courts prevalent during the time of Shivaji in Maratha territory were

Dharmasabha, Brahman Sabha, and Deshak Sabha deserve mention. The Brahmin Sabha was

composed of distinguished scholars of high character. Sometimes scholars from

Banaras were invited for deciding complicated cases. One of these councils was

called by Shivaji to decide his Kshatriya origin and the right to have a coronation

with Vedic ceremonies. The Deshak Sabha was generally composed of Deshmukhs,

Deshpandes, Patils, Balutas of the villages, and Shete-Mahajans of the towns

included in the Pargana. Officers of the Pargana like Hawaldar, Thanedar, Samaubat,

Karkun, Sabnis, Chitnis, Karkhanis, Sargrohs, Naikwadis, etc. used to be members of

this council. A case relating to several villages was decided by it. If a party was

dissatisfied with the decision of the village panchayat, it could request the

re-hearing of the case by the Deshak Sabha. Dharmasabha seems to be headed by

Panditrao, the head of the ecclesiastical department, who had the right to

countersign all documents issued by the king relating to Achara, Vyavahara, and

Prayaschitta - the three parts of the Dharmashastras. Some revisionary power was

vested in the Panditrao; otherwise, he would not give his approval to the decisions

of the secular courts. [27]

Most importantly, Shivaji conferred a great deal of judicial autonomy upon the

people as recommended in the ancient law books of India. According to Sukra,

cultivators, artisans, artists, usurers, corporations, dancers, ascetics and thieves

should decide their disputes according to the usage of their profession. Thus,

Shivaji allowed all civil and even ordinary criminal cases to be decided by people’s

courts at the local level. In villages, the complainant took his plaint to the Patel

who after trying to get the dispute settled through his own influence, called on a

few village elders to sit together and hear the parties. The saraunsh which was the

summary of the evidence was noted by the village writer and the execution of which

was the duty of the mamladar. The main object aimed at was amicable settlement and

arbitration. If arbitration failed, the case was transferred for a decision to a

panchayat, appointed by the Patel in the village and by the shete mahajan, or

leading merchant in urban areas. An appeal lay from the decision of a panchayat to

the mamladar, who usually upheld the verdict unless the parties concerned were able

to prove that the panchayat was prejudiced or corrupt. In important suits, however,

it was the duty of the mamlatdar to appoint an arbitrator, the members of which were

chosen by him with the approval and often at the suggestion, of the parties to the

suit. In such cases, the panchayat’s decision was subject to an appeal to the Peshwa

or his legal minister, the nyaydhish.[28] Thus, the system of panchayats

left a good deal of autonomy in the legal administration at the local level.