Kingship & Harsha, the King

Harsha was the greatest monarch of his time in India. His accession to the throne

against all adversity and the way he unified most of northern India were

remarkable. At the time when his father Prabhakaravardana died, Harsh and his

elder brother Rajyavardhana were defending the western frontier of India from

the Hun’s invasion. Rajyavardhana, being the eldest son ascended the throne

although he is said to have been treacherously murdered.[4]

After his brother’s death, Harsh become the king but the incidents connected

with his accession throw light on the fact that despite a younger brother of a

dead king, the selection of Harsha as the next ruler was discussed among his

ministers and they duly elected him on account of his qualities. When the news

of Rajyavardhana’s murder was received, the chief minister Bhandi, who was a

near relation of the royal dynasty and whose power and reputation were high and

of much weight, addressed the assembled ministers, “The destiny of the

nation is to be fixed today. The old king’s son is dead: the brother of the

prince, however, is humane and affectionate, and his disposition,

heaven-conferred, is dutiful and obedient. Because he is strongly attached,

to his family, the people will trust in him. I propose that he assume the

royal authority, let each one give his opinion on this matter, whatever he

thinks.” All ministers and officers agreed to Bhandi and exhorted

Harsha to assume the royal authority. [5]

Harsha immediately after becoming a king declared war on Shashanka and also

embarked upon a campaign of Digvijay, i.e. conquest in all directions. Harsha

declared that all the Indian kings must either pledge their loyalty to him or

meet him in war. A proclamation which, as Banabhatta says, Harsha engraved soon

after his accession seems to address both feudatories and independent princes.

Harsh promulgate:

“Let all kings prepare their hands to give tribute, or grasp swords; to

seize the realms of space or cohwries; let them bend their heads or their

bows, grace their ears with my commands or their bowstrings; crown their

heads with the dust of my feet or with helmets.” [6]

Harshvardhan waged incessant warfare with the five largest kingdoms of his time

for six years thus enlarging his territory. He increased his army, bringing the

elephant corps up to 60,000 and the cavalry up to 100,000, and reigned in peace

for thirty years without raising a weapon.[7] The Digvijaya must have

resulted in some annexations but it left numerous rulers semi-independent who

generally acknowledged the suzerainty of Harsha.

Although the fabric of the Indian states was weakening at the time of Harsha due

to the advent of feudalism in the polity, nevertheless, Harsha ruled with all

distinction according to the rules set by the Dharmashasta literature. Most of

the Hindu rulers of India up to the recent past followed the enlightened

conception of kingly duties prescribed to them by ancient lawgivers. No ordinary

ruler would have dared and no conscientious one would have liked to infringe so

strong a tradition which had the legacy of Dharmasastra, Nitisastra, and

Arthasastra. Kautilya, himself says that the king’s first duty should be the

promotion of the happiness of his subjects as therein laid his own happiness.

The ruler, says Sukra, has been made by Lord Brahma the servant of the people

getting his revenue as his remuneration. His sovereignty is only for protection.

Harsh not only pursued these high ideals but also strove to maintain them. He

constantly toured his vast empire to be fully enlightened about the true

condition of his people and remedy their grievances. He gave his personal

attention to all matters of importance as described by Banabhatta and Hsuan

Tsang.[8]

Hsuan Tsang notes in his account that Harsha is seen constantly on the move

except during the rainy season. Incessant travelling, whether on military

expeditions, administrative tours, or for religious motives, was part of the

personal conduct of the administration. Harsha divided the day into three

periods, devoting one to affairs of government and two to religious works. Hsuan

Tsang also informs us that Harsha found the day too short for him and he forgot

to sleep and take food in his devotion to good works. Noteworthy of Harsha’s

governance to mention is that he ruled in conjunction with his sister Rajyashri

because the dominion of his husband’s kingdom was merged with the territory of

Harsha’s empire. [9]

Council of Ministers

The success of the Vardhan dynasty was largely due to the Harsha himself. The

ancient Hindu tradition as described in the Nitisastras was closely followed

that lays down the rule or more appropriately the tradition, that the king

should be assisted by a privy council consisting of the heads of departments.

Under Harsh rule, next to him, i.e., sovereign ranked the chief ministers of the

empire, who probably constituted a Matriparisad or council. The Council of

Ministers wielded considerable power in the matter of state and even the

election of the king was in their hands.[10] Even during the lifetime

of the monarch, the council used to exercise great powers in matters of

administration because Harsha was often touring the country. There can be no

doubt that though Harsha’s government was personal in one sense the royal

authority was by no means despotic. The council of ministers possessed

considerable powers against which no monarch could act. [11]

We find in Harshacharita a very interesting episode where king Prabhakarvardhan

summoned his both sons in and gave them an advice that never to fall in the trap

of sycophant ministers. The occasion was of appointment of the brothers

Kumaragupta and Madhavagupta, sons of the Malwa king, close associate of his two

sons as “they are men found by frequent trials untouched by any taint of vice,

blameless, discreet, strong, and comely.” Prabhakarvardhan affectionately

addressing Rajyavardhan and Harshvardhan said,

“My dear sons, it is difficult to secure good servants, the first essential

of sovereignty. In general mean persons, making themselves congenial, like

atoms, in combination, compose the substance of royalty. Fools, setting

people to dance in the intoxication of their play, make peacocks of them.

Knaves, working their way in, reproduce as in a mirror their own image. Like

dreams, impostors by false phantasies beget unsound views. By songs, dances,

and jests unwatched flatterers, like neglected diseases of the humours,

bring on madness. Like thirsty catakas (subordinate police), low-born

persons cannot be held fast. Cheats, like fishermen, hook the purpose at its

first rise in the mind, like a fish in Manasa. Like those who depict

infernos, loud singers paint unrealities on the canvas of the air. Suitors,

more keen than arrows, plant a barb in the heart.”[12]

Apart from the incidents connected with the accession of Harsha which make clear

that all the chief ministers met together to discuss important questions, we

have many more instances indicating the role of Matriparisad in important

matters of the state. For example, when Rajyavardhana went to fight the murderer

of his brother-in-law and accepted their invitation to come to their camp after

victory, he was doing so on the advice of his council of ministers. It was wrong

advice which resulted in the murder of the young king. This proves that the

council of ministers was also in charge of making decisions about war and

foreign policy.[13]

Harsacarita indicates that ministers were consulted individually by the king. In

Harsacarita, the chief military officer— ‘foremost in every fight’ — is called

Senapati. The commander of the cavalry was another high military officer.

Mahasamdhivigrahika was the foreign minister. Mahabaladhikrita is mentioned as a

great office in supreme command of the army. The Pramatri is a counsellor and

another high officer of the state. Also, it looks like feudatories worked in

high positions directly under the suzerain. The supposition is strengthened by

the mention of Mahasamantas and Maharajas in the same breath as regular officers

in Harsha inscriptions. [14]

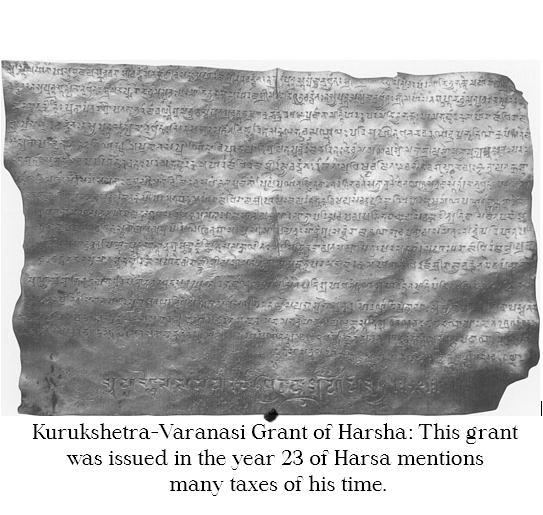

Administrative Units

The inscriptions and Harshacharita present a hierarchy of officers and

administrative divisions to which they are assigned. The territory of the empire

was called a rajya, rastra, desa, or mandala made up of a number of

administrative divisions. Usually, they appear to be as follows in descending

order where Bhukti represents the province, Visaya was the district, Pathaka

signifies the smaller territorial unit perhaps like a modern-day taluka, and

Grama or village was the smallest unit. The Visaya had its administrative

headquarters called Adhisthana or town. [15]

The villages were in charge of their headmen. The government did not interfere

in the autonomy of the villages which they enjoyed for a long time. The larger

territorial divisions were undoubtedly controlled by the centre. But

decentralisation also worked for better management of various units. Personal

inspections by Harsha kept the territorial units in order, and there was

coordination between the central government and the administrations of the

provinces. [16]

The Bureaucracy (State Functionaries)

Under Harsha’s reign, a well-ordered bureaucracy appears to have existed. The

governor of the bhukti or province designated as Uparika-maharaja is sometimes

put in charge of the king’s son. The governor is also called by other names such

as Gopta, Bhogika, Bhogapati, Rajasthaniya, and Rashtriya or Rastrapati. The

provincial governor appointed his subordinate officials, described as

tan-niyuktakas. He appointed his Visayapati (or the divisional commissioner) to

whom apply the titles of Kumaramatya and Ayuktaka. Many high officers were

associated at the provincial level such as Mahasamantas, Maharajas,

Daussadhasadhanikas, Pramtaras, Kumaramatyas, Uparikas, and Visayapatis.

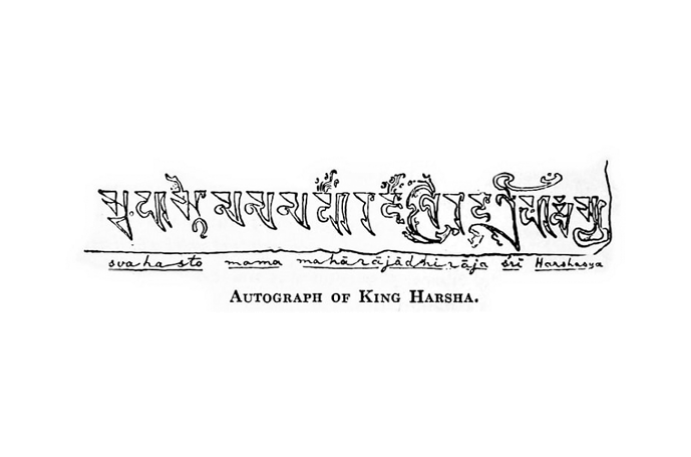

Drangikas were the city magistrates. [17] When the king’s orders were

personally delivered to the feudatories and provincial officials, they were

called svamukhejna. Sometimes they were also signed by the king himself. The

Banskhera Plate grant of Harsha is signed by him and described as ‘given under

my own hand and seal’ (svahasto mama maharajadhirajasri Harsasya).

[18]

The staff of the local government included Mahattaras (the village elders),

Asta-Kuladhikaranas (probably officers in charge of groups of eight kulas or

families in the village), Gramikas (the village head-men), Saulika (in charge of

tolls or customs), and Gaulmika (in charge of forests or forts).[19]

As the empire become more decentralized and feudal, a set of many new officers

appeared in seventh-century India. The officer in charge of land revenue was

called Dhruadhikaranas whereas Bhandagaradhikrita was the treasurer, Talavataka,

probably the village accountant, tax-collector called by the name Utkhetayita

and most importantly Pustapalas and Akaspatalika, those who keep the record and

on whose efficiency depends the stability of the administration. The enlightened

character of the administration is also shown in its maintenance of a separate

Department of Records and Archives called Akaspatalika. It is attached to the

records office called Aksapapla, under the departmental head called the

Mahakaspatalika. The Department of Records included the clerks who wrote down

the records or documents and called the Diviras, and Lekhakas. The documents

referred to as Karanas were kept in the custody of the registrar called

Karanika. [20]

Besides these officers with specified functions, there were also general

superintendents called Survadhyakas, whose offices employed high-born officers,

the kulaputras, to help them with the responsibility of their work. Among other

civil officers, we may note those attached to the royal household such as the

Pratihara, Mahapratihara - the chief guard or usher of the palace, Vinayasura,

whose function seems to have been to announce and conduct visitors to the king,

the Shapati samrat, probably ‘superintendent of the attendants of the women’s

departments’, Pratinartaka, a bard or herald, and the like. Among other

officers, one of the most notable is the Dauhasadhanika, one who is entrusted

with the difficult duty of the high police officer. He was assisted by

Ayuktakas, subordinate officers, and Catas or police. [21]

Apart from these officers, the machinery of local government provided a place

also for the non-official element to help in the administration. The Visayapati

administered with the assistance of an advisory council called samvyavaharati

consisting of (1) Nagara-Sresthin, most likely representing the city; (2)

Sarthavaha standing for the trade guilds; (3) Prathama-Lulika the craft-guilds;

and (4) Prathama-Kayastha perhaps the chief secretary, or the representative of

the kayasthas or scribes as a class. [22]