Content

[6] H. N. Sinha, Soverignty in Ancient Indian Polity, Luzac and Co., London, 1938, p. 20.

[7] Beni Prasad, The State in Ancient India, Stud in the Structure and Practical Working of

Political Institutions in North India in Ancient Times, The Indian Press Ltd., Allahabad, 1928,

p. 49

[8] Bandyopadhaya, p. 161.

[9] F. E. Pargiter, Ancient Indian Historical Tradition, Oxford University Press, London,

1922.

[10] A. S. Altekar, State and Government in Ancient India, Motilal Banarasidas, Banaras, p. 16

and J. Gonda, Ancient Indian Kingship from the Religious Point of View, Nuven: International

Review of History of Religion, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Jan., 1957), pp. 24-58.

[11] R. C. Majumdar, History and Culture of Indian People, Volume I, Vedic Age, George Allen &

Unwin Ltd, London, 1953, pp. 427-431.

[12] Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa 1. 3. 2. 2.

[13] Hemchandra Raychaudhuri, Political History of Ancient India [m the Accession of Parikshit

to the extinction of the Gupta dynasty, Universit of Calcutta, 1923, p. 83-87.

[14] Narayan Chandra Bandyopadhaya, Development of Hindu Polity and Political Theories, Part I

From the earliest times to the Growth of Imperialist Movement, Messers and Cambray, Calcutta,

1927, p. 176.

[15] Om Prakash Singh, "Gana-Samgha" States in Historical Perspective, Proceedings of the Indian

History Congress, Vol. 57, 1996, pp. 132-140.

[16] See, Episode 1, Surajya Sanhita (TV Series 2019) telecast on Sansad TV

[17] R. C. Majumdar, History and Culture of Indian People, Volume I, Vedic Age, George Allen &

Unwin Ltd, London, 1953, pp. 431-43

[18] See, Sanjeev Kumar Sharma, Taxation and Revenue Collection in Ancient India: Reflections on

Mahabharata, Manusmriti, Arthasastra and Shukranitisar, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016.

[19] Narendra Nath Law, Aspects of Ancient Indian Polity, Oxford, 1921, pp. 169-170.

[20] Narayan Chandra Bandyopadhaya, Development of Hindu Polity and Political Theories, Part I

From the earliest times to the Growth of Imperialist Movement, Messers and Cambray, Calcutta,

1927 pp. 159-160.

[21] Pramathnath Banerjea, Public Administration in Ancient India, Macmillan & Co., Limited,

London, 1916, p. 127.

[22] B. G. Bhatnagar, “Local Self-Government in the Vedic Literature,” The Journal of the Royal

Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 3, Jul., 1932, pp. 529-540.

[23] R.S. Sharma, A History Textbook for Class XI, National Council of Educational Research and

Training, 2005, p. 83.

[24] Makhan Lal, Ancient India Textbook for XI, National Council of Educational Research and

Training, 2002, pp. 94-95.

[25] A. S. Altekar, State and Government in Ancient India, Motilal Banarasidas, Banaras, p.

96-97.

[26] Narendra Nath Law, Aspects of Ancient Indian Polity, Oxford, 1921, p. 26.

[27] Chhandogya Upanishad - 6 Reflections by Swami Guubhaktnanda on the Series of 19 Lectures

by Swamini Vimalanandaji Director-Acharyaji,Chinmaya Gardens, Coimbatore to the 15th Batch

Vedanta Course at Sandeepany Sadhanalaya, Powai, Mumbai April 17th – May 8th, 2012 pp.

72-73.

[28] Beni Prasad, Theory of Government in Ancient India, The Indian Press Ltd., Allahabad, 1927.

See also, Arthur Anthony Macdonell and Arthur Berriedale Keith, Vedic Index of Names and

Subjects, Vol. II, John Murray, London, 1912.

[29] R. C. Majumdar, History and Culture of Indian People, Volume I, Vedic Age, George Allen &

Unwin Ltd, London, 1953, p. 436.

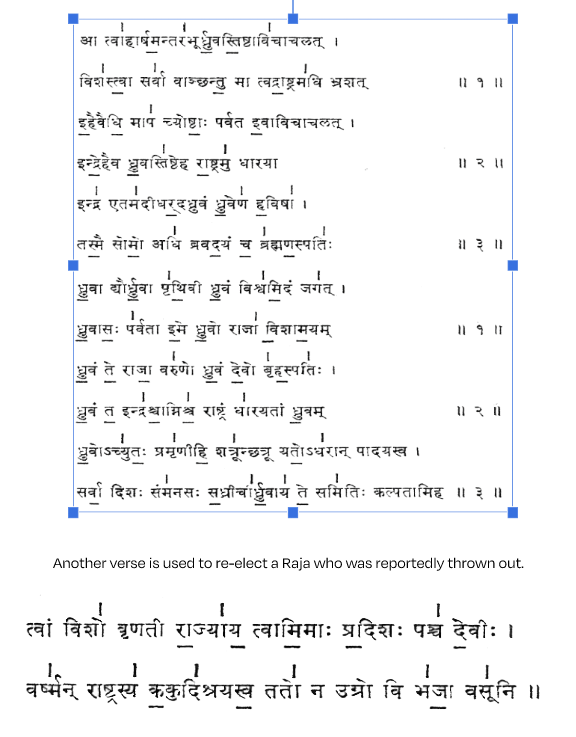

Pictures

William Dwight Whitney, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons